The Leverage Point You've Been Optimising Around

I was 19 when I first encountered one of the most powerful ideas I’d ever ignored.

Together with my small class of 16, we walked into a dark classroom in an unfamiliar part of campus. The air felt stuffy. We had no idea what this course would cover — its description bore little resemblance to the obvious math and sciences required for food technology and process engineering.

The lecturer entered, an old man with one of those classic leather suitcases in hand. With surprising conviction, he declared our first assignment: read the novel The Goal by Dr. Eliyahu M. Goldratt.

What followed was a display of enthusiasm about Goldratt’s work and its apparent underappreciation in industry. We played manufacturing simulation games that left us mostly confused. We just wanted to pass the exam. Little did we know that we were being introduced to a very powerful idea indeed — one that I wouldn’t fully appreciate until many years later, when I realised it explained not just factory floors, but any system with a goal, including the system of my own mind.

The Theory of Constraints

In his 1984 business novel The Goal: A Process of Ongoing Improvement, Goldratt introduced the world to the Theory of Constraints (TOC).

The premise is surprisingly obvious when stated:

Focus on identifying the single most important limiting factor (the constraint) that prevents a system from achieving its goal, then systematically improve that constraint until it is no longer the limiting factor.

TOC rests on a foundational principle that any complex system operates as a chain of interdependent processes, and the performance of the entire system is limited by its weakest link (the constraint). Therefore, focusing improvement efforts anywhere but the constraint will not significantly improve the overall system’s performance. Often, it simply wastes resources.

In manufacturing contexts where TOC originated, constraints were primarily physical bottlenecks in production lines that limited overall output. One slow station determines the throughput of the entire factory, regardless of how efficient every other station becomes. You can optimise twenty steps in your process, but if the twenty-first step remains the bottleneck, your total output doesn’t budge.

The underlying principle, however, extends far beyond factory floors.

Why It Works: The Mark of a Good Explanation

Before we explore the applications of TOC, it’s worth asking: what makes it worth our time? Why trust this framework over the countless other self-improvement approaches?

According to Critical Rationalism — the epistemological framework pioneered by Karl Popper and developed further by David Deutsch — a good explanation must satisfy three criteria: it must be hard-to-vary (falsifiable), possess deep reach (apply across diverse domains), and demonstrate problem-solving power (yield measurable results).

TOC satisfies all three.

Hard-to-vary: TOC makes testable, falsifiable predictions. If you improve a non-constraint resource, overall system throughput will not increase. If you improve the actual constraint, throughput will increase. This is a specific claim you can test.

Deep reach: Although originally developed for manufacturing plants, TOC applies across fundamentally different domains without conceptual modification. Goldratt and his team extended it to project management, accounting, and supply chains. But the reach extends further still – into domains Goldratt may never have considered.

Problem-solving power: When correctly applied, TOC consistently yields measurable improvements in system performance. It’s not just intellectually elegant; it’s pragmatically reliable.

Here’s what makes this particularly interesting for us: our personal lives are full of systems too.

Our daily routines operate as a system of habits and behaviours — the morning person whose productivity constraint isn’t their 5am wake-up but their inability to say no to interruptions. Our health and fitness function similarly — the committed exerciser whose progress stalls not from lack of training but from chronically inadequate sleep. Same goes for our relationships — the caring partner whose connection suffers not from lack of love but from an unaddressed need for control.

But perhaps most critically for our purposes, our mind itself is a system — an interconnected network of mental models, beliefs, and cognitive patterns that determine both our internal experience and external results. This is where we’ll focus.

The Bottleneck in Your Mind

Your Cognitive System

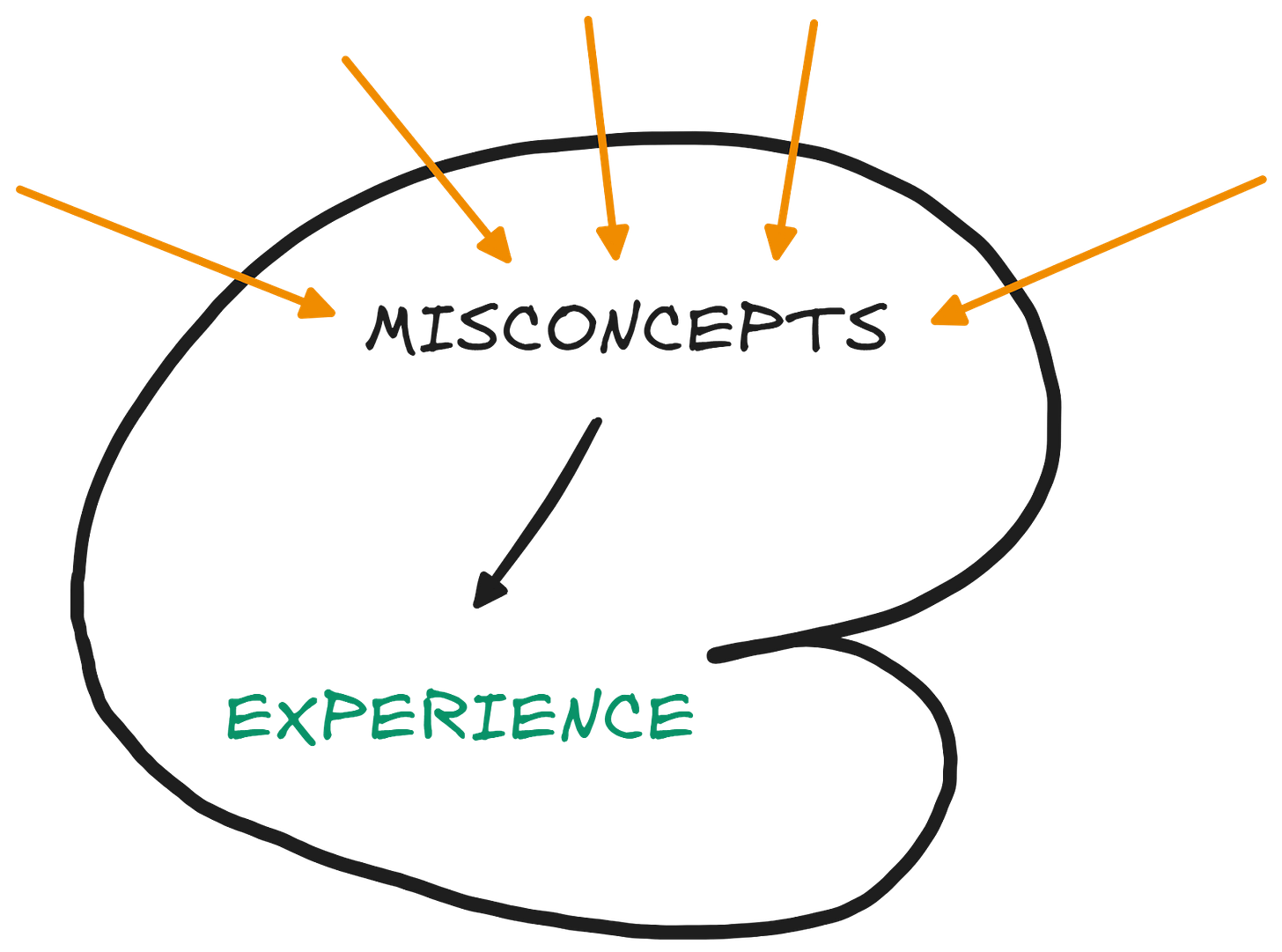

Consider how your mind actually operates. You possess a set of interconnected mental models — what we call misconcepts as a reminder of their inherent fallibility. These misconcepts are either inherited (from evolution or culture) or deliberately acquired through learning and experience.

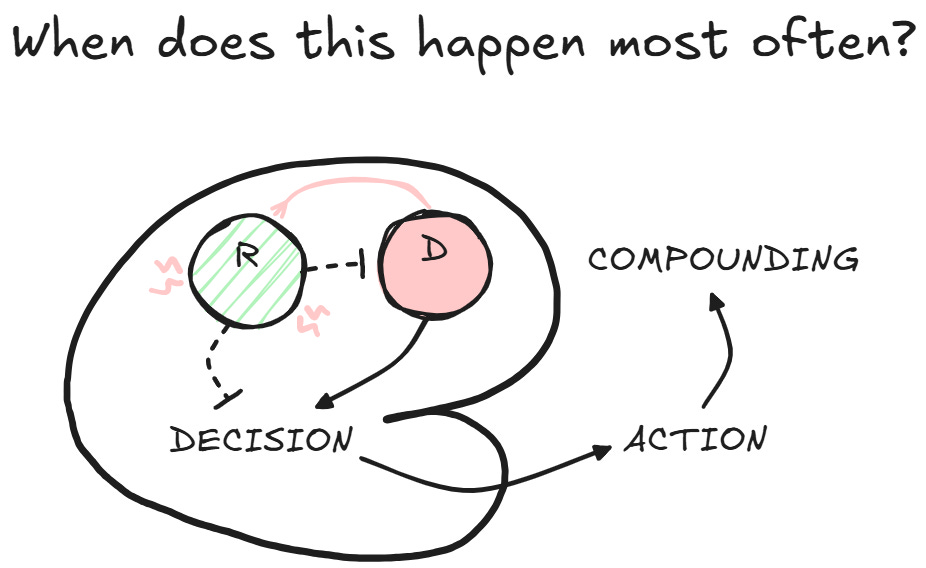

Your mind toggles between two modes: System 1 (your automatic, default misconcepts at work) and System 2 (your reflective, rational misconcepts at work). Together, these misconcepts form an interconnected system that produces two types of output: your internal experience (how you feel) and your external results (what you achieve).

The set of misconcepts we hold may not always serve us well, especially the inherited defaults. Some actively work against our best interests.

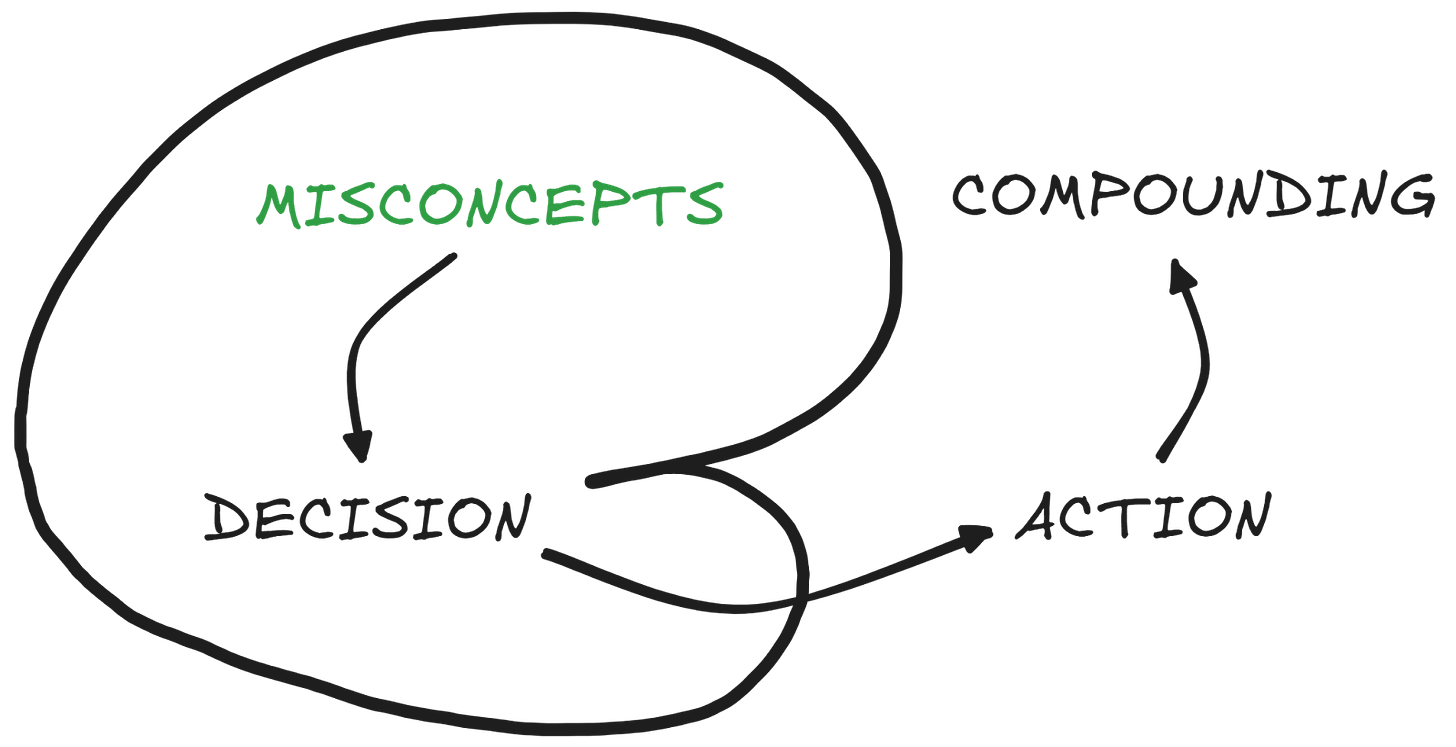

Here’s the crucial insight: Default misconcepts that prevent us from achieving our goals (internal or external) are bottlenecks that can be systematically diagnosed and resolved. These are your cognitive constraints.

The thing is, we often inherit an array of default misconcepts that do not serve us — self-limiting beliefs, emotional patterns, cognitive habits etc. All of these are potential areas for improvement. But among these, there is typically one single greatest constraint impeding your progress right now.

Common Cognitive Constraints

What do these constraints look like? Some common examples include:

An approval-seeking constraint - you seek external validation through people-pleasing, even when it undermines your own well-being, authentic goals, and long-term fulfilment.

A fixed mindset constraint - you hold rigid beliefs about your capabilities that prevents you from attempting challenges where you might look incompetent, limiting your overall potential in the long run.

A social comparison constraint - you constantly compare yourself to others resulting in perpetual misery and feelings of inadequacy.

An ego constraint - you’re so preoccupied with protecting your self-image that you avoid feedback, resist admitting mistakes, and reject opportunities where you might be challenged.

You might have many constraints that need addressing — I certainly did and still do. But there will be one that represents the biggest bottleneck to your current goals and well-being.

By focusing on fixing that constraint first, you extract the highest return on your finite time and energy, unlocking more capacity to work on the next constraint in an iterative cycle of self-improvement.

Why This Matters

These constraints function like hidden taxes on your limited mental energy. Addressing them is how you unlock more capacity than you thought possible.

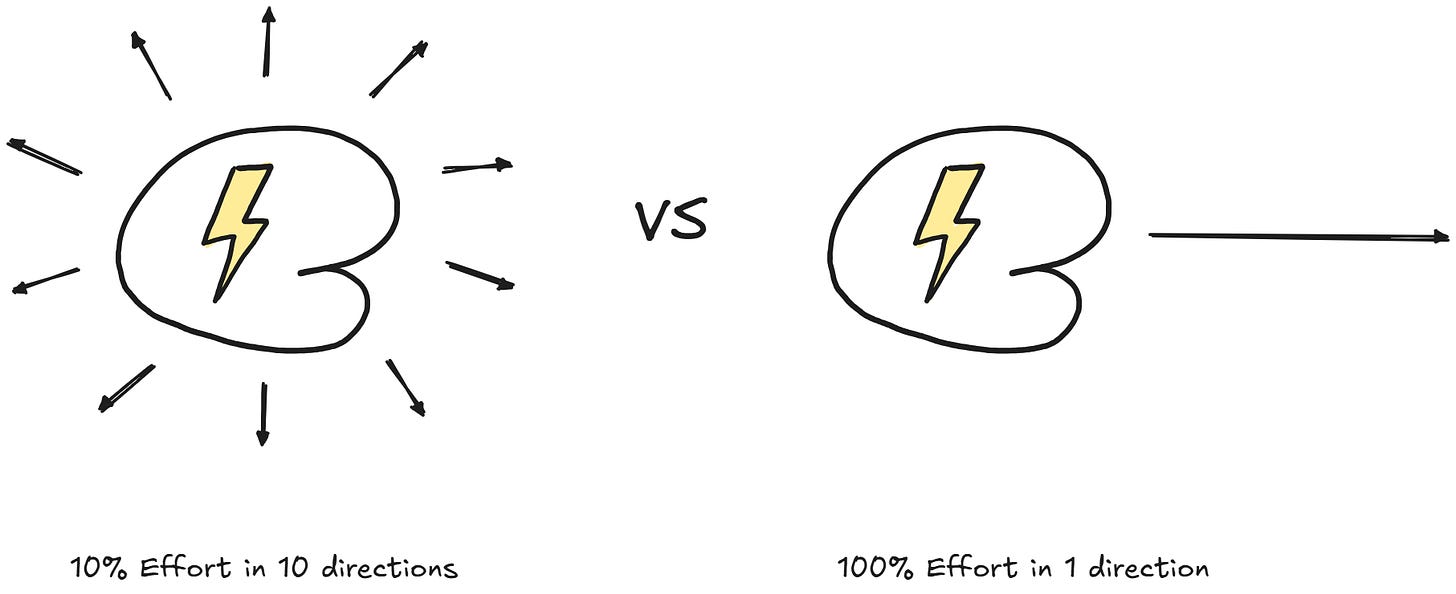

Addressing the single bottleneck yields asymmetric returns compared to diffuse optimisation efforts, which is the typical approach in self-improvement.

This explains why you can be intelligent, disciplined and knowledgeable but still plateau. Why you find yourself “stuck” despite all your self-improvement efforts. You’ve been working on your constraints, just not the constraint limiting your cognitive system.

The path to exponential improvement isn’t working on everything. It’s finding the one thing that’s constraining everything else. So how do we make this actionable?

The Protocol

Applying TOC to our cognitive system requires a systematic approach. As you might’ve already guessed, first you identify the constraint, then you address only this constraint, then you repeat. Simple, but not easy.

As Richard Feynman warned: “The first principle is that you must not fool yourself — and you are the easiest person to fool.”

This is particularly true when identifying our own constraints.

Step 1: Identify the Constraint

The tricky part about finding your bottleneck is that multiple other constraints will be clamouring for your attention. You’ll feel tempted to work on them all at once or on the easiest and most obvious one. But TOC argues — and my experience supports — that the biggest gain comes from addressing the bottleneck first.

So how do you find this bottleneck? The diagnostic tool we’ve developed and refined over years of application is as follows:

Your single biggest constraint is the constraint that causes the most psychological pain in your life right now.

Reflect on the past week and identify the most common frustration or psychological pain you experienced. What was the underlying misconcept generating that pain? That’s your constraint.

To support you in your reflections, here are questions that have helped us identify our constraints.

Start here:

What caused me the most emotional or psychological pain the past week, and why?

Dig deeper:

What pain do I keep encountering despite changing circumstances?

Which belief once protected me, but now confines me?

Find the leverage:

Which of my defaults, if addressed, would render everything else easier?

If I could only fix one mental pattern, which would unlock the most growth?

What 20% of mental patterns are causing 80% of my problems and unhappiness?

The constraint often reveals itself through repetition and cross-domain presence. It’s the pattern that follows you everywhere, influences everything you do, limiting throughput across multiple life systems simultaneously.

Step 2: Fix the Constraint (and subordinate everything else)

Once you have identified your bottleneck, it becomes your primary focus. Everything else gets temporarily subordinated.

This is where the approach becomes counter-intuitive. We always feel like we have to improve all our flaws simultaneously, but working on anything other than the bottleneck gives you a lower return on your limited resources. You end up not making significant progress on any fronts.

When you feel tempted to work on other constraints, remind yourself that the best use of your limited time and energy is on the point of highest leverage. The point that will give the most return.

Warren Buffett observed: “The difference between successful people and really successful people is that really successful people say no to almost everything.”

This includes saying no to working on other legitimate constraints, at least until you’ve elevated the bottleneck.

Give yourself permission to focus on just one constraint and de-prioritize other self-improvement work temporarily.

Fixing a default cognitive pattern takes time and effort. But once shifted, it provides a foundation that serves you for a lifetime, generating compounding returns — if not in external results then in internal peace and contentment.

Systematically shift the default cognitive constraint you’ve identified until a new default takes root. This isn’t quick work. It’s leverage work.

Step 3: Repeat (because the constraint moves)

The work doesn’t end with the first constraint.

Once your primary constraint ceases to be limiting, a new constraint naturally emerges. This isn’t failure — it’s progress. Solving one constraint reveals the next. The system’s capacity just expanded. Now a different factor becomes the limiting element.

This is how we can systematically improve and extract the highest return on our limited life resources: through iterative optimisation.

Self-improvement isn’t arriving at some fixed state of mind. It’s continuously identifying and addressing the next constraint in an ongoing process of system elevation.

Let me make this more tangible by sharing how this played out in my own life.

For years I tried to tackle all my cognitive constraints simultaneously — comparison, people-pleasing, perfectionism. When I finally identified comparison as my bottleneck (the pattern causing the most pain at that point in time), I gave myself permission to focus on only that.

What couldn’t shift when I tried tackling everything at once finally shifted. Once it did, I had mental bandwidth to address the next constraint. Sequential solving, not parallel processing.

After years of applying this iterative cycle, much of the defaults that once caused me immense daily suffering have shifted. I feel more at peace internally than I ever have in my life. The constraints haven’t disappeared entirely, I still have defaults I’m working to shift. The difference is that I now have much more capacity to work on things that matter to me and show up as my best self.

Failure Modes

When I first applied this approach, it wasn’t straightforward. I would misidentify my constraint or get distracted by other patterns mid-process. Here’s what I’ve learned about the most common failure modes:

Failure Mode 1: The Comfortable Misidentification

Sometimes we identify a constraint that feels tractable rather than the one causing the most pain. We choose the constraint we’re ready to face, not necessarily the constraint that’s actually limiting us.

If you’re working on your “constraint” but the familiar pain persists across domains, ask yourself with radical honesty: Am I avoiding naming the real constraint because it feels too confronting?

One diagnostic I’ve found helpful is to ask someone you trust deeply — a partner, parent, or close friend — “If you could change just one tendency of mine, what would it be?” Their answer might be uncomfortable. It might also be right.

Failure Mode 2: The Equal Constraints Situation

Occasionally you’ll identify 2-3 constraints that feel roughly equivalent in their limiting effect. If this is the case, don’t expend energy trying to precisely rank them. Pick one and begin. The process of working on any of your top constraints will often reveal which is actually most limiting.

Movement generates clarity.

Failure Mode 3: The Distraction by New Constraints

As you work on your identified constraint, you’ll notice other patterns that seem urgent. This is normal — and it’s a trap. The pull to work on emerging constraints mid-process is strong, especially for high-agency individuals accustomed to tackling problems immediately.

The antidote: Remind yourself that these aren’t new constraints — they were always there, just hidden behind the primary bottleneck. Note them, then return focus. They’ll still be there when you’ve elevated the current constraint.

Making This Actionable

By applying TOC to your interconnected system of mental models, you spare yourself the inevitable overwhelm of trying to fix everything at once (which never works by the way).

You find the one thing to fix. Then move to the next. Then the next.

This approach guarantees substantially greater progress than scattering your efforts everywhere and seeing progress nowhere. It’s not just more effective — it’s more sustainable. You’re not maintaining a dozen parallel self-improvement projects. You’re sequentially solving your actual limiting factors.

The constraint is there. It’s operating right now, limiting your throughput, generating the pain you’ve been feeling, and preventing the progress you’ve been seeking.

The question isn’t whether you have a constraint — we all do.

The question is whether you’ll identify it.

Your Turn

This week, set aside 10 minutes for this reflection:

Work through the diagnostic questions in Step 1 above. Look for the pattern that appears most frequently, causes the most pain, and shows up across multiple domains of your life.

That’s your constraint. That’s where your leverage lives.

You don’t need to fix it immediately. You just need to name it clearly, then commit to making it your primary focus until it’s no longer the limiting factor in your system.

Then — and only then — move to the next one.

What constraint have you been working around instead of working on?