Staying In The Game

Navigating the Trough of Disillusionment

Most people don’t quit because starting is hard. They quit because continuing looks pointless.

You’ve heard it a thousand times: just be consistent, show up every day, and results will follow. So you did. You built the habit, proved you could maintain it. And now, months in, you’re staring at minimal results wondering what you’re doing wrong.

You’re not doing anything wrong.

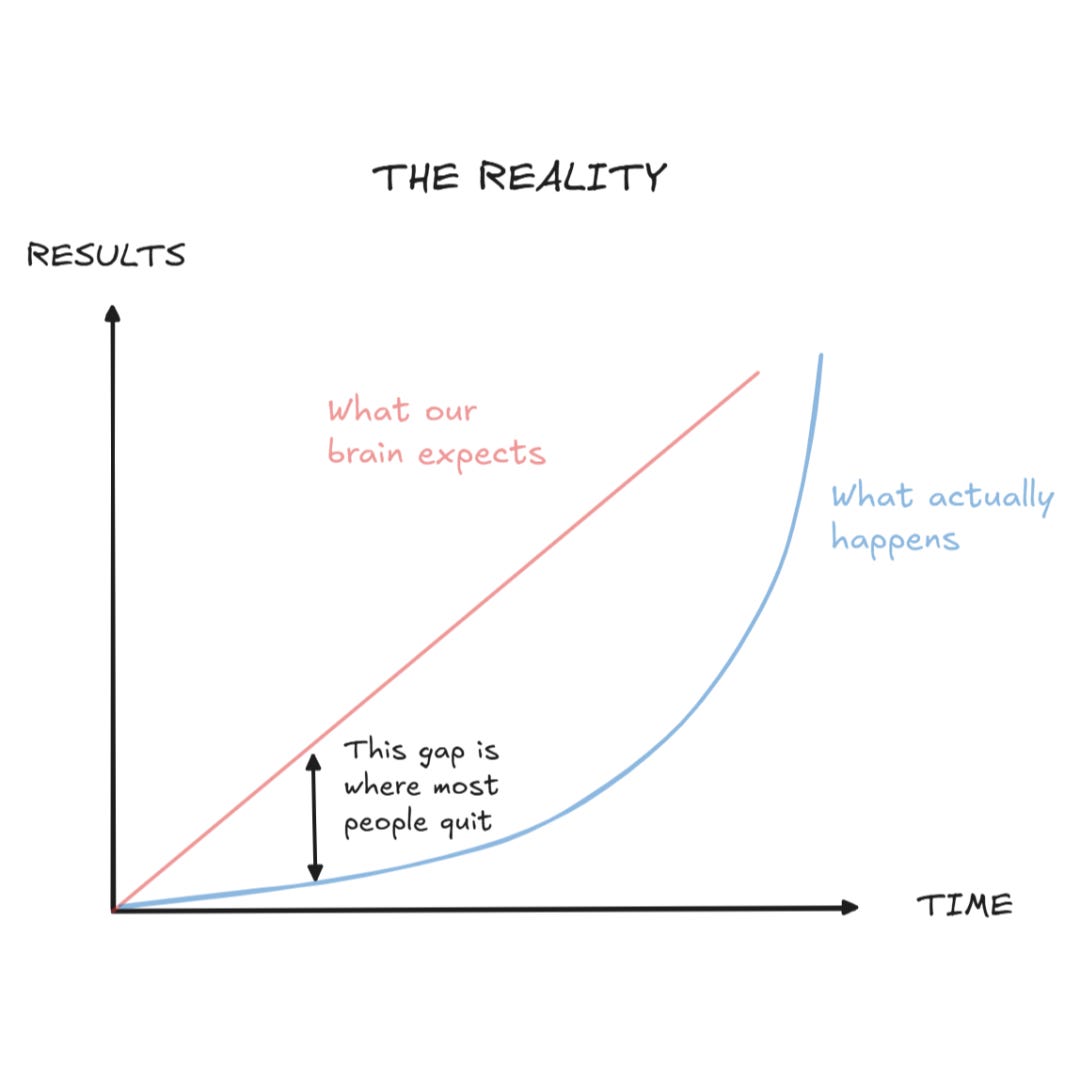

You can be perfectly consistent for months and see almost nothing happen. The gap between effort and outcome stretches far longer than any motivational quote prepared you for.

This is where most people quit. Not in the beginning, but here, in the flat part of the compounding curve that precedes every breakthrough.

Understanding the mathematics of why this gap exists might be what helps you stay in the game. It helped me.

The Dangerous Middle

You’ve already cleared the first hurdle. The physical habit is established. But now you’re facing a different test: psychological endurance without visible reward.

This is the most dangerous point in your journey — not because you can’t be consistent, but because you’re considering stopping perhaps moments before the compounding inflection point arrives.

The challenge is no longer building the habit. It’s maintaining belief in the habit when compounding hasn’t revealed itself yet.

Why Progress Feels Slower Than It Is

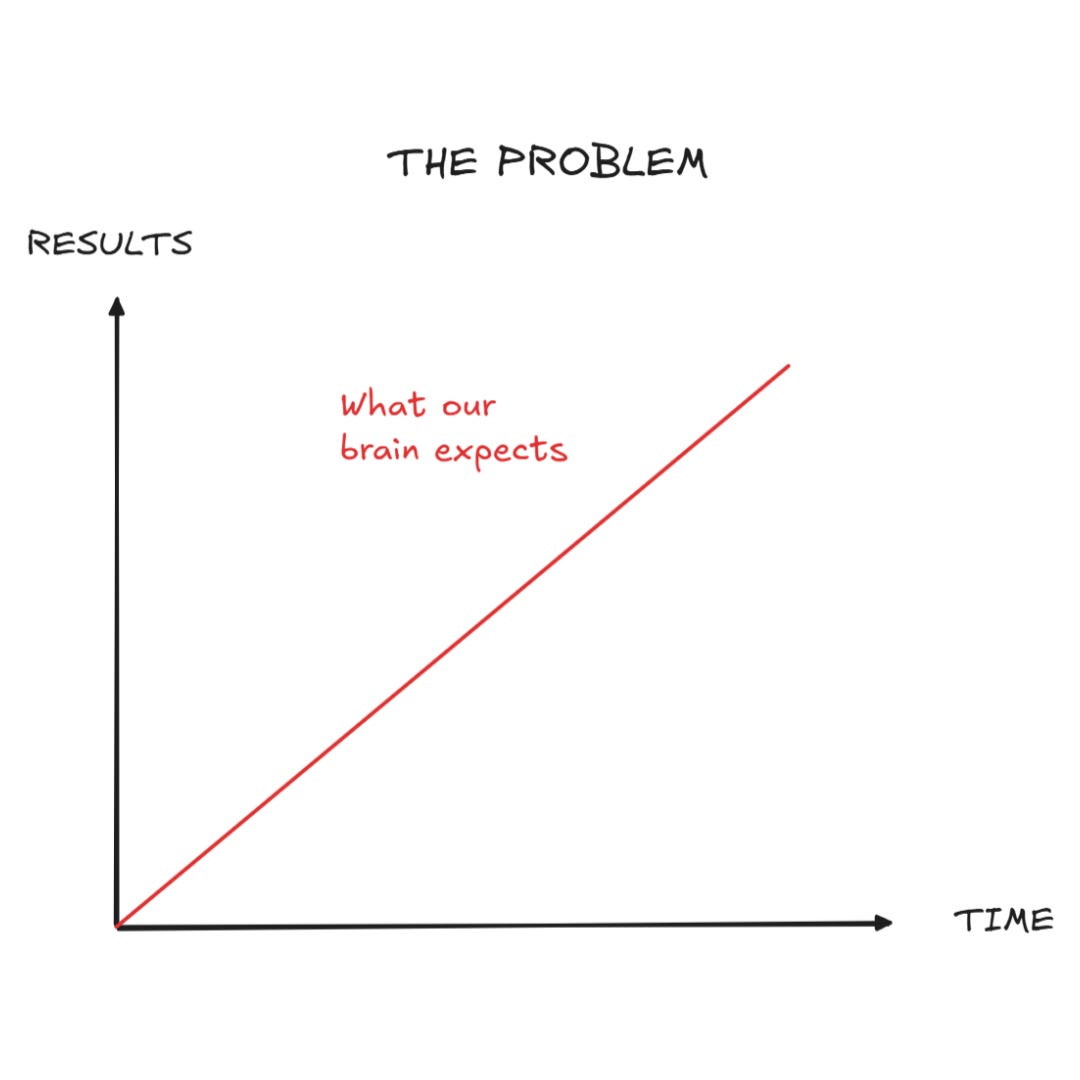

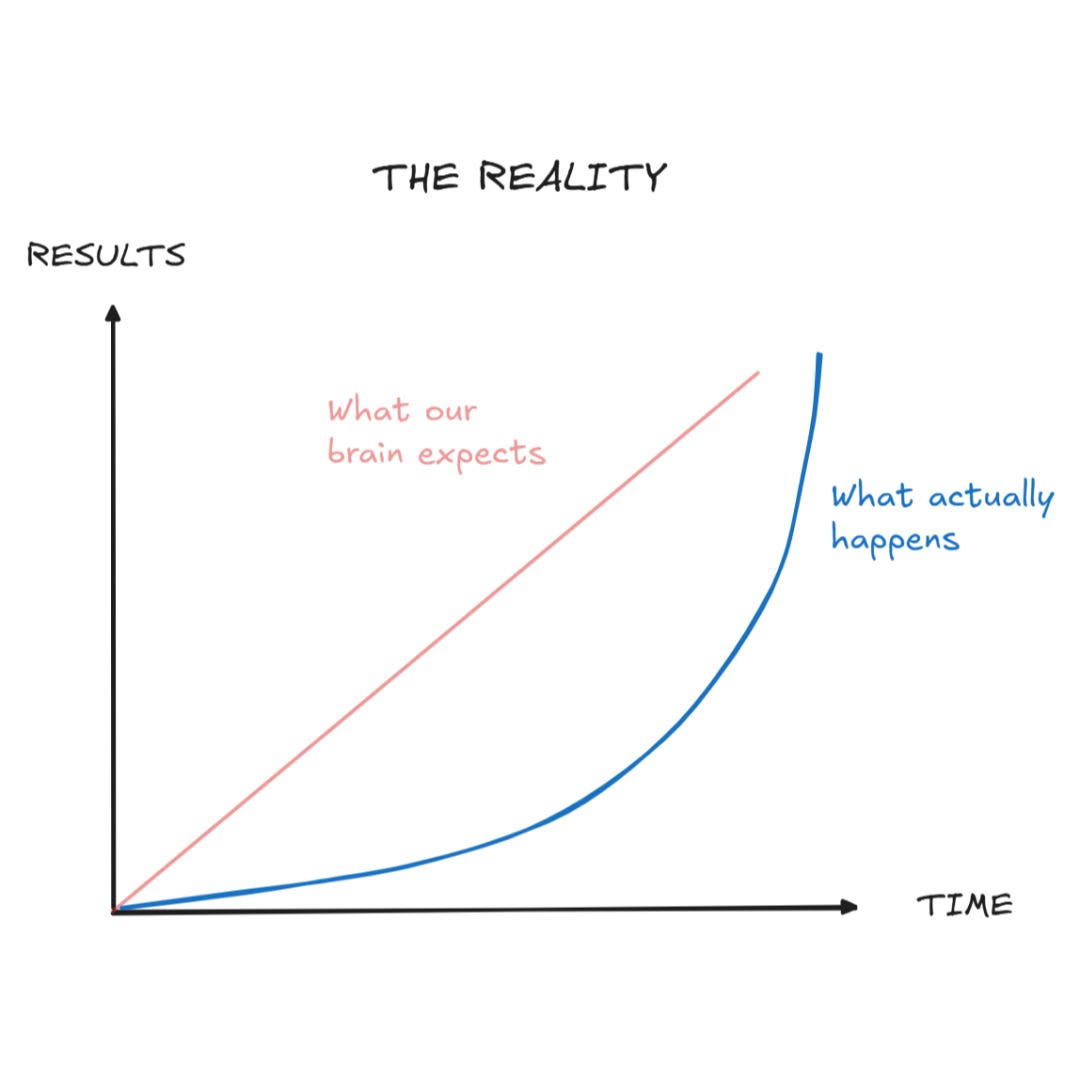

Here’s what’s happening: our brains think linearly while reality compounds exponentially. We expect to get one unit of result for each unit of effort. But compounding doesn’t work that way.

In the early days, effort starts large and results start small. The gap between what you’re putting in and what you’re getting out feels discouraging. This lasts far longer than you’d expect, even if you accommodate for it in your expectations.

I nearly quit here myself. Multiple times. What kept me going wasn’t blind faith or relentless optimism, it was understanding mathematics.

Compounding works like this: imagine you improve by just 1% each attempt. At the start, you put in effort and get back 1.01. Next time, you don’t just improve on your original baseline — you improve on the new foundation you’ve built. So you get 1.0201, then 1.0303, then 1.0406. The gains feel tiny because they ARE tiny. That’s why progress feels flat.

But here’s the key: each small gain becomes your new starting point. You’re not building from zero every time; you’re building from yesterday’s progress.

After 100 attempts? You’re at 2.7048 — nearly 3 times your starting point.

After 365 attempts? You’re at 37.78 — from 1% daily improvements.

Think of a snowball rolling down a hill. The first few rolls pick up just flakes of snow. But once it’s bigger, each roll adds massively more — same effort, bigger snowball, exponentially more snow sticking to it.

The inflection point isn’t a matter of if, but when. But it only arrives if you keep going.

“Compound interest is the eighth wonder of the world. He who understands it, earns it; he who doesn’t, pays it.” — Albert Einstein

Every great outcome is just ordinary actions repeated until they compound into something extraordinary. Consistency feels hard because it looks like nothing is happening... until suddenly everything is happening.

When you feel discouraged, visualise the compounding curve. Those early days? That’s the flat part where you are right now. But you’re on the right curve. The inflection point is inevitable if you keep going.

The Ones Who Didn’t Quit

The compounding curve doesn’t discriminate. It works for writers, inventors, chefs and salesmen — anyone willing to persist in the game. History is full of ordinary people who refused to quit during the flat part of the curve and that refusal is what made them extraordinary.

Let me show you what staying in the game actually looks like.

The Writer Who Wrote for 3,000

Andy Weir is one of the most successful science fiction authors of our generation, but his success was anything but expected. Before The Martian became a Hollywood blockbuster, it was simply a hobby project on a personal website. For a decade, Weir worked as a software engineer by day and a writer by night, posting chapter after chapter of a story about an astronaut stranded on Mars to an audience of 3,000 science nerds.

He wasn’t writing for a payout — he was writing for the puzzle. Those 3,000 readers corrected his chemistry, and he tightened the plot. When they complained about reading the blogs on the computer, he compiled it into a 99-cent Kindle e-book just to make their lives easier.

After uploading it to Amazon, the e-book didn’t just sell, it exploded. It rocketed up the bestseller charts, caught a literary agent’s eye, and led to a major publishing deal and Hollywood blockbuster. He stayed in the game not because he was winning, but because he loved playing.

The Inventor Who Failed 5,126 Times

In the late 1970s, James Dyson grew furious with his vacuum cleaner — it lost suction the moment the bag filled up. Unlike most people who would simply buy a new bag, Dyson started building.

For fifteen years, supported by his wife’s art classes and drowning in debt, he built prototype after prototype. 5,126 of them, to be exact. Each one failed. He faced rejection from every major manufacturer and skepticism from the entire industry.

But Dyson wasn’t chasing applause, he was chasing a solution. It took 5,126 failed prototypes before number 5,127 finally worked. His multi-billion-pound empire wasn’t built on instant genius. It was built on refusing to accept that “good enough” was good enough. The only difference between a crazy idea and a brilliant invention is the endurance to keep building.

The Chef Who Iterated for 70 Years

Jiro Ono, subject of the documentary Jiro Dreams of Sushi, is known as one of history’s greatest sushi chefs. But his three Michelin stars weren’t the result of sudden talent. It was the result of relentless, monotonous consistency.

For seventy years, Jiro has done the exact same thing every day: making sushi. Same spot, same routine, constantly seeking microscopic improvements. He massages octopus for forty-five minutes, not thirty, just to ensure perfect softness.

He’s not a celebrity chef chasing television contracts — he’s a craftsman who has done the same thing for seven decades. His three Michelin stars weren’t the goal, they were the byproduct of refusing to leave the game.

The Salesman Who Heard 1,009 Nos

At sixty-five, most people are looking to retire. Harland Sanders was broke, living off a $105 monthly Social Security cheque, with nothing but a fried chicken recipe and a determination to sell it.

Armed with a pressure cooker and a blend of eleven herbs and spices, he hit the road. He slept in his car, shaved in petrol station bathrooms, and walked into restaurants offering to cook his chicken for the owners. The answer was almost always “no.” In fact, he heard “no” 1,009 times before his first “yes.”

He stayed in the game when society told him it was time to quit, and that persistence turned a single recipe into the global KFC empire. His inflection point arrived late, but only because he refused to stop knocking on doors. Colonel Sanders proves that the compounding curve respects effort, not age.

All of these figures — an engineer, an inventor, a chef, and a salesman — shared one trait: they survived the trough of disillusionment. They understood, perhaps subconsciously, that lack of immediate results wasn’t a signal to stop, but a deposit into an account that would eventually pay compound interest.

But how did they do it? What kept them going when the scoreboard showed nothing?

“The person who fails the most wins. Not because failure is the goal, but because the person willing to fail the most is the person who’s willing to stay in the game the longest.” — Seth Godin

Why They Didn’t Quit

Why did they keep going when results stayed flat? Because they stopped looking at the scoreboard and started looking inward.

When you rely on extrinsic motivation — money, applause, immediate results — you’re at the mercy of the world. When results don’t come, your fuel runs out. Extrinsic motivation is fragile.

The secret to surviving the trough of disillusionment is shifting your fuel source to intrinsic motivation. Intrinsic motivation survives the silence.

For Andy Weir, it was curiosity — he loved the puzzle.

For James Dyson, it was problem-solving — refusing to accept mediocrity.

For Jiro Ono, it was mastery — the spiritual need to perfect a craft.

For Harland Sanders, it was conviction — unshakeable belief in his work.

“The trick is to enjoy the process. The outcome is out of your control. Focus on the input, and the output will take care of itself.” — Naval Ravikant

None of them waited for the compounding curve to validate them. They brought their own energy to the game.

If you want to reach the inflection point, stop asking, “Is it working?” and start asking, “Is this worth doing?” If the answer is yes, you stay in the game. And if you stay in the game, the mathematics says you will eventually win.

Your actions are always compounding you towards one destination or another. Staying in the game compounds. But so does stopping — just in a different trajectory. The choice isn’t between compounding and not compounding; it’s about which direction you’re compounding towards.

This is what I’ve tried to internalize: When things get hard, I don’t feel dejected — I feel confirmed. This difficulty is exactly what I expected. It’s evidence that I’ve stayed in the arena long enough for the initial dopamine hit to fade. This is the real test, and I’ve already decided to pass it.

Outlasting Uncertainty

The breakthrough is mathematically inevitable, but the timeline isn’t. You can be consistent, shift to intrinsic motivation, iterate intelligently and still not know when the inflection point will arrive.

This is where intrinsic motivation becomes crucial. Dyson and Weir weren’t just enduring the uncertainty, they were energized by the work itself. Dyson loved solving the problem. Weir loved the craft. When the work itself is meaningful, the uncertain timeline becomes bearable. You’re not white-knuckling your way through the trough, you’re genuinely curious about what each attempt might reveal.

And here’s what makes this powerful: their intrinsic motivation didn’t just help them stay in the game, it made them better at playing it. They weren’t just repeating, they were iterating. Dyson wasn’t building prototype 1 five thousand times, he was building 5,126 prototypes, each one incorporating what the previous failure revealed. Weir’s final novel worked because 3,000 readers helped him course-correct along the way.

This is intelligent persistence. If you stay in the game and keep iterating, compounding is inevitable. You just can’t control exactly when.

What Game Are You Playing?

So here’s my question for you: What game are you currently playing? And more importantly, is your motivation for playing it strong enough to survive the trough?

If you’re only in it for external validation, the trough will outlast your fuel. But if you can genuinely find meaning in the work itself, you might just stay in the game long enough for the mathematics to work in your favour.

This is how you sustainably stay in the game — because being in the game itself becomes its own reward.

“When you’re interested in something, you just want to do it. And if it works out, great. If not, you still had fun doing it.” — Rick Rubin

The flat part of the curve isn’t where you quit. It’s where you prove you’re serious.

The trough of disillusionment isn’t a sign you’re failing. It’s a sign you’re exactly where everyone who eventually succeeds has been. The only question is whether you’ll stay long enough to find out what happens next.